image courtesy Timber Press

Emily Dickinson's Gardening Life, The Plants and Places That Inspired the Iconic Poet

.

If you have any comments, observations, or questions about what you read here, remember you can always Contact Me

All content included on this site such as text, graphics and images is protected by U.S and international copyright law.

The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of the site copyright holder.

Emily Dickinson's Gardening Life, a book review

Thursday, 26 September 2019

Unlike other people in my family I have little interest in genealogy. To know when someone was born, if they married, perhaps had children, then died is like an outline of their life. It doesn't tell us how they lived, what they loved (spouse and children, presumably) to turn them from mere statistics into a person. With her latest book

image courtesy Timber Press

Emily Dickinson's Gardening Life, The Plants and Places That Inspired the Iconic Poet

Marta McDowell brings Emily Dickinson to life as a gardener, one who was as enchanted and passionate about the plants and flowers of the Homestead's gardens, the wildflowers of the field, and those she grew in a little conservatory. As a child, Emily Dickinson studied botany (along with other subjects) at Amherst Academy. She made a herbarium, sixty-six pages with 424 pressed plants, several to each page, carefully labeled with Latin names following the Linnaean system. Today we think of her, first and foremost, as a poet. In her lifetime, it was the Homestead's garden that was admired.

Deftly weaving together poems, plants, and historical detail, the book takes us down the same pathways that Emily Dickinson trod. The chapters and their plants are grouped by the seasonal changes: early and late spring, early, mid- and late summer, autumn, and winter. For example

She slept beneath a tree -

Remembered but by me.

I touched her Cradle mute -

She recognized the foot -

Put on her Carmine suit

And see!

.

15, 1858

This early poem, which Marta calls a sort of schoolgirl puzzle, describes a bulb as asleep, forgotten by all except the gardener. Because it wakes up with carmine red petals, and there are few red-flowered spring bulbs it is most likely to be a tulip.

image provided by Marta McDowell

The Homestead in spring, peony shoots emerging, and tulips wearing carmine suits.

Using words to paint a picture, Emily Dickinson with her poems, Marta McDowell in this book, suggesting how to travel back in time to the days when The Homestead stood on an unpaved street with horse and carriage traffic going by. The flowers of spring move on from early bulbs to the dainty heart's ease, Viola tricolor.

One of the flowers in her herbarium, on a page with other violets.

Flowers from the garden or from the wild would be little bouquets,

we're told, sent with a note to friends and acquaintances. Sweet.

Each season's chapter begins with an historical, a biographical portion, setting the stage for what is to come when we reach the plants. Interspersed with the author's text and Dickinson quotes are a diversity of illustrations - old photographs, botanical illustrations, herbarium pages, and of course, appropriate poems. As befits the author's knowledge of plants and botany, Marta provides information about the plants - the healing properties of bloodroot, Sanguinaria canadensis, and a charming little image of this spring ephemeral is one such.

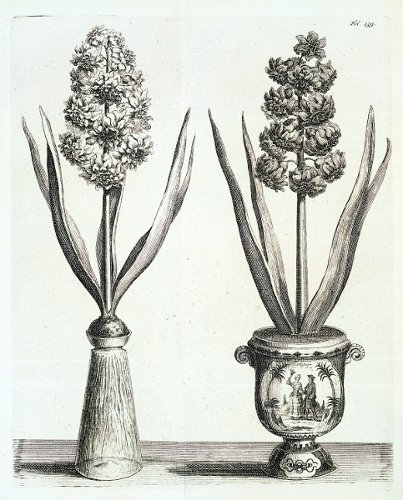

While Emily Dickinson kept no garden notebooks or plant lists, the letters she sent to friends and family often makes mention of what is happening in the garden. Her niece, Martha Dickinson (who married, then later divorced Alexander Bianchi, a captain in the Imperial Russian Horse Guards), remembered "carpets of lily-of-the-valley and pansies, platoons of sweetpeas, hyacinths, enough in May to give all the bees of summer dyspepsia. There were ribbons of peony hedges and drifts of daffodils in season, marigolds to distraction, a butterfly utopia." Marta weaves the letters people received from Emily Dickinson into the book, for - alas - the letters that came to her were destroyed when she died, as she demanded.

image provided by Marta McDowell

Winter comes, and the bulbs buried in the ground are sleeping.

There was a small conservatory, unheated. On cold nights she

would open a window in the house and stoke its stove. With

just a few steps she could, Emily wrote, inhabit the Spice Isles.

image provided by Marta McDowell

Hyacinths would be forced on windowsills, a rainbow of flowers

to soothe the gardener restlessly waiting for spring's arrival.

I suppose the book could be read from cover to cover. For me, it's more like a conversation with a friend, a gardening friend. Dip into a season, set the stage, read about her life, what she is doing in the garden. The book has the interwoven biography of a poet and gardener. There's an annotated list of plants cultivated by the Dickinsons: annuals and perennials; trees, shrubs, and woody vines; fruits and vegetables; other plants mentioned or collected by Emily Dickinson. There are both common and Latin names, where mentioned in poems, letters, the herbarium or others, if it is native, and brief notes about the majority of them. Multiple pages for sources and citations are provided. Does this sound scholarly and dull? Scholarly it is, but far from dull. It's a gardener's life, one who happens to be a poet.

Marta at the lecturn for her talk at the Cross Estate's Talk and Tea.

In the interest of full disclosure, I must say that

Marta and I have been friends and colleagues for many years,

as well as gardeners talking and trading plants back and forth.

A copy of this book was provided by the publisher

Back to Top

Back to September 2019

Back to the main Diary Page